This project researches the principles of pre-colonialism versus colonial aesthetics and practices to understand what it means to decolonize the built environment. The design seeks to call attention to the history of the land and Middlebury College's

colonial past by incorporating the values of modern Indigenous architecture. This includes emphasizing the structure's connection to place, community, integration with the land, and developing a universally inclusive environment.

SITE PLAN

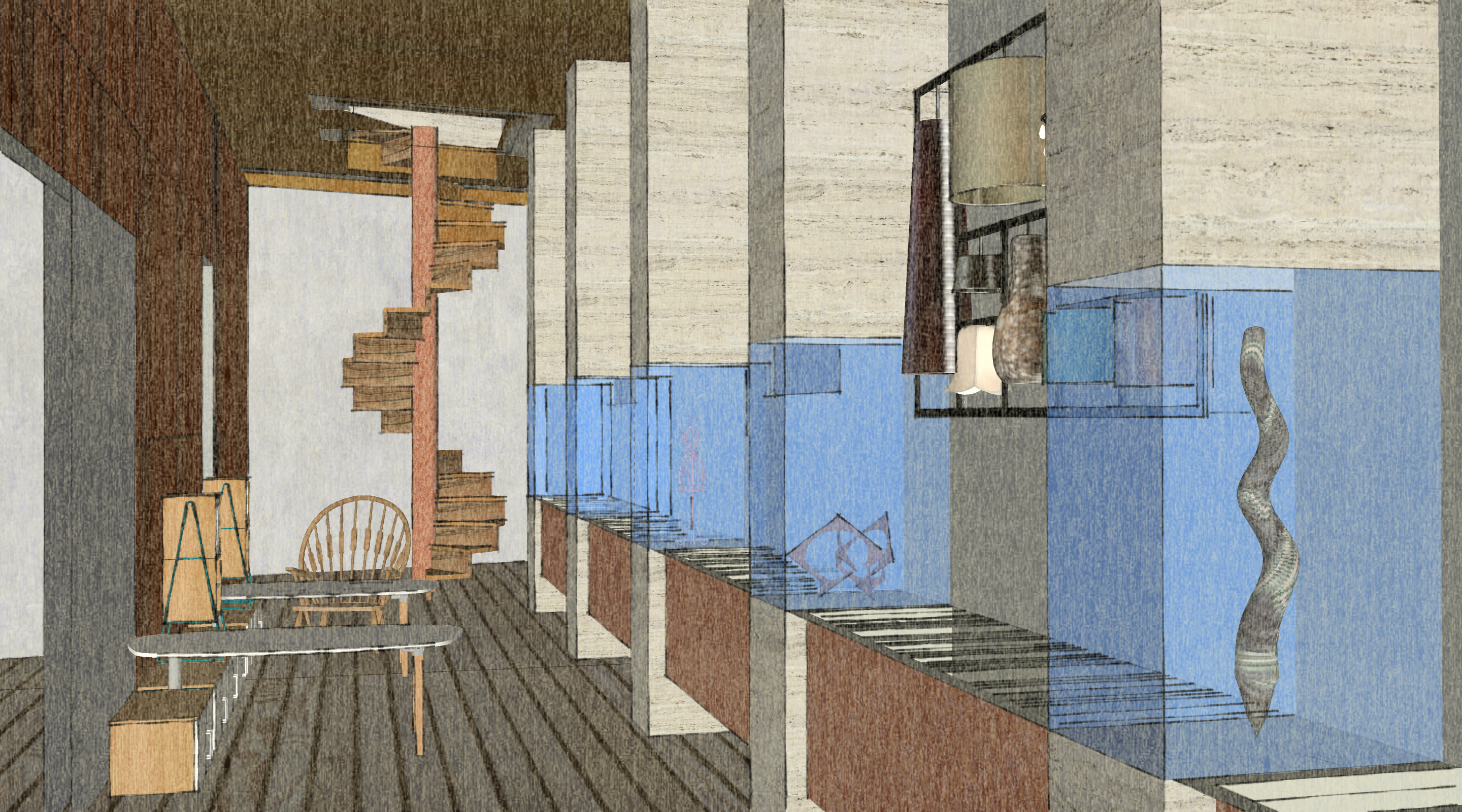

The design explores what it means to decolonize inaccessible spaces like the museum and the archives through design. Though it forms a liminal space between the land and the built, it does not attempt to construct a sublime architectural

experience rooted in wealth and privilege yet, strives to create a comfortable and accessible space for creative, academic, and environmental engagement.

Creation/Educational Spaces

How do we create a conversation between the viewing of and the historical understanding and creation of objects?Gathering Spaces

How do we blur the boundary between informal gathering and structured exhibition space to form a casual and accessible interaction with objects?Museum Spaces

How can exhibition design limit gallery spaces from reinforcing feelings of exclusion and neo-colonization? How can we combat the inclusion of mostly Western-centric objects from highly colonial epochs when we are not the curators of the museum?Archive Spaces

How do we highlight the voices of marginalized communities that have been buried within the archives and make their stories more accessible to the general public?Outdoor Landscape

How do we respond and engage with the land through design to diffuse the boundary between the built and the natural environment?SECTION

DIAGRAMMING SPACES OF DECOLONIZATION

PERSPECTIVES

This monument functions as a recognition of the Indigenous Abenaki community within Vermont and aims to shed light on Middlebury’s colonial past and present. The monument embodies the idea of universal inclusivity: the concept that humans are

only one part of a larger system by creating a rainwater system

to water a garden composed of the Seven Sisters of Abenaki Indigenous Agriculture. It exists as a space for students and the Middlebury neighborhood, including Abenaki members of the community, to come together for leisure and cultivation.

The structure emulates the Seven Sisters in the way they support one another to thrive. I created a system of parts that work together to create this functioning living monument. It consists of a mesh netting that captures water droplets; framing that provides structural support; a funnel that collects direct rainwater, water droplets from the mesh and serves as a dew conductor; a tank to store the harvested water channeled from the funnel and an irrigation system below to distribute the water when needed.

The monument will use corrugated metal and other non-rotting materials for the tank and framing to protect the water; however, the seating area around the structure will be made of a weathering wood that adapts to the environment over time. All of these ideas are preliminary. I wanted to stray away from incorporating any more Indigenous symbolism, aesthetics, or forms into the sculpture because if it were to be built, I would like it to be a collaborative process with the Abenaki community of Vermont.

Web-based map designed for the Twilight Project’s Patriarchal Power and the Built Environment on Campus Space Fellowship.